Process vs. Performance

One of the hardest parts of investing is intelligently evaluating how things are going. This is especially true for publicly traded companies (stocks) or strategies (like mutual funds) that invest in them. The problem is financial assets tend to fluctuate wildly from year to year. Consequently, investors simply looking at past returns (like everyone does), are very likely to be misled.

A slightly more sophisticated investor may ignore the quarter to quarter, or even year to year swings, knowing that it’s better to judge on a longer-term basis, say 3-5 years. Surprisingly, even longer-term averages can be disproportionately impacted by a big swing in a single year.

A perfect example is an international stock strategy I follow quite closely. Since its 1992 start, the strategy has been one of the best in its category, outpacing the benchmark in excess of 3% (a wide margin in the investment business).

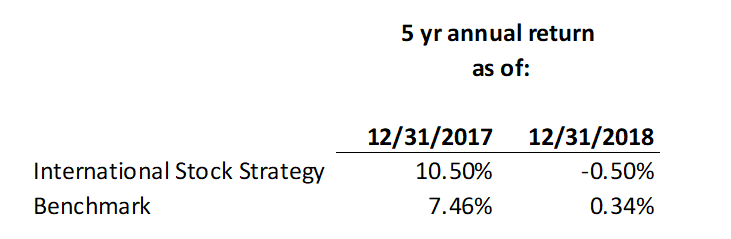

More recently, the manager’s performance has been rocky. As of the year-end 2017, the strategy had generated a 5-year average return of 10.5% and outpaced its benchmark by over 3%, consistent with its long term average. Investors seeing these figures at the end of 2017 couldn’t have been more pleased. However, just a year later, things changed dramatically.

You may remember that 2018 was the first full year stock prices declined in the US since 2008. The sell-off was much worse in the international markets. The aforementioned strategy found itself right in the middle of the tumult and turned in a particularly weak year falling 23.4%. What’s more significant is the impact this one year had on the 5-year average.

At year-end 2018, the exact same strategy highlighted above found itself with a new 5-year average return of -0.50% and lagging it’s benchmark by nearly 1.0% annually. Think about that, in one year, the 5-year average flipped from a double digit return and material outperformance to a negative return and lagging performance!

This isn’t a statistical one-off of an obscure fund. These things happen regularly, even to the greatest investors. The reason is, to escape the averages in investing, your portfolio must be different from the market. Unfortunately, being different means there will inevitably be periods, sometimes extended, when your portfolio falls out of favor.

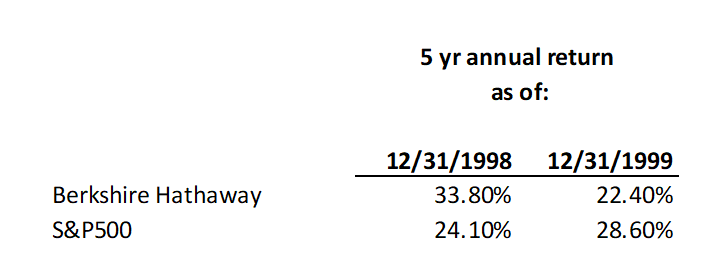

Even Warren Buffett’s Berkshire Hathaway hasn’t been immune. In 1998, Berkshire’s stock price did what it was known for, appreciate significantly more than the broader market (52.2% vs. 28.6% for the S&P500). At year-end, the stock had a 5-year average return of 33.8% walloping the S&P500’s 24.1%.

But in 1999, amidst the internet/tech bubble, Berkshire Hathaway’s stock price got killed. The stock was -19.9% for the calendar year vs. 21.0% for the S&P500. That’s an over 40% spread! Investors should ask themselves if they could hold an investment that lagged the broader stock market by 40% in a given year!

More importantly, consider how one year drastically changed the 5-year average. At year-end 1999, Berkshire’s 5-year average now lagged the S&P500 by a material margin, 22.4% to 28.6%. Investors should likewise ask themselves if they could hold a strategy that lagged the broader market by 6% on average for five years.

The point of these examples is highlighting how past performance can be very misleading, even on a relatively long-term basis. This creates a problem for investors because performance (returns) is what everyone is ultimately seeking; yet, relying on it solely to assess how things are going can lead to extremely poor conclusions.

The better approach, though far from perfect, is to focus on process. That is, if you’re going to invest with an asset manager (such as a mutual fund), it’s essential to understand what they are doing. If you don’t know what they are doing and why, it’s impossible to assign any real meaning to the returns. This is especially important for a portfolio that has been weak (because that’s when people start stirring to make a change).

Legendary investor Howard Marks wrote a 14-page dissertation on the subject of achieving superior investment returns in 2006 titled, “Dare To Be Great.” One paragraph especially struck me:

Underperforming managers – Retain or fire…or add money? That’s the real question. Good investors hold fast to their approach and discipline. But every approach goes out of favor from time to time, and the manager who adheres most firmly can do the worst. A lagging year or two doesn’t make a manager a bad one…maybe just one whose market niche has been in the process of getting cheap. But how often are managers given more money when they’re in a slump (as opposed to being fired)?

Experienced investors know that the markets can turn against even the greatest asset managers or individual companies. In a cruel twist, these periods can precede some of the best streaks of out-performance. That’s exactly why Howard Marks says, counterintuitively, the real question to consider of underperforming managers is whether to add money.

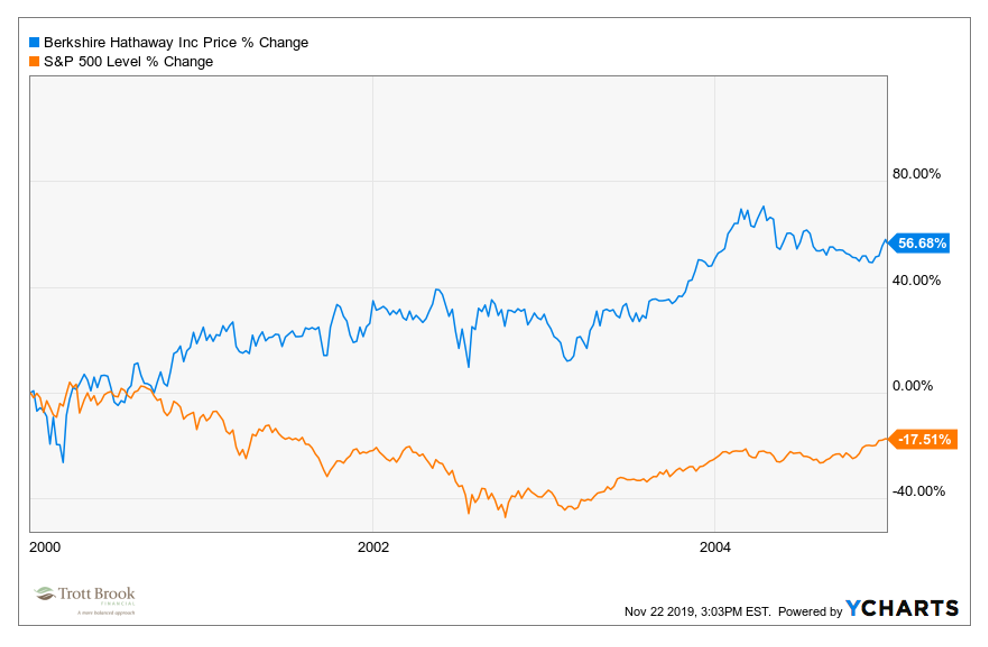

Returning to Warren Buffett’s Berkshire Hathaway, consider what happened during the 5-year period following the rough year in 1999:

It turns out that the temporary weakness presented a great opportunity to buy as the markets broadly went south and Berkshire marched ahead. The question is, how could investors have come to that conclusion?

If you actually read Buffett’s 1999 letter to shareholders, you’d see that nothing devastating happened that year. The company did experience a one-off underwriting loss in its insurance operations, but generally speaking, nothing had changed at Berkshire. Investors who actually took the time to understand what was happening more likely would have recognized that if anything, 1999 presented a chance to buy Berkshire at an attractive price.

I could give another half dozen examples of money managers that, after a period of weak performance, came back with extraordinary results. The point is performance itself really doesn’t tell you anything. What’s essential is understanding the strategy being implemented and the logic behind it. Although this context doesn’t guarantee perfect foresight, it is what’s most important for interpreting returns and making judgements about the future.

Frequently, periods of weakness present great buying opportunities. But without the proper context, investors are simply left guessing which usually lends itself to buying high and selling low.

Disclosure

Advisory services offered through Trott Brook Financial, Inc., a registered investment advisor. Securities offered through LaSalle St. Securities, LLC, a FINRA/SIPC member broker/dealer. Trott Brook Financial, Inc. and LaSalle St. Securities, LLC are unaffiliated separate legal entities.